Radio has long been essential to the spread of popular music, especially before the Internet age.

Every artist hoped to have his or her music played on the radio. Airplay could turn a new artist into a star. Musicians who failed to get played on the radio, however, rarely became stars.

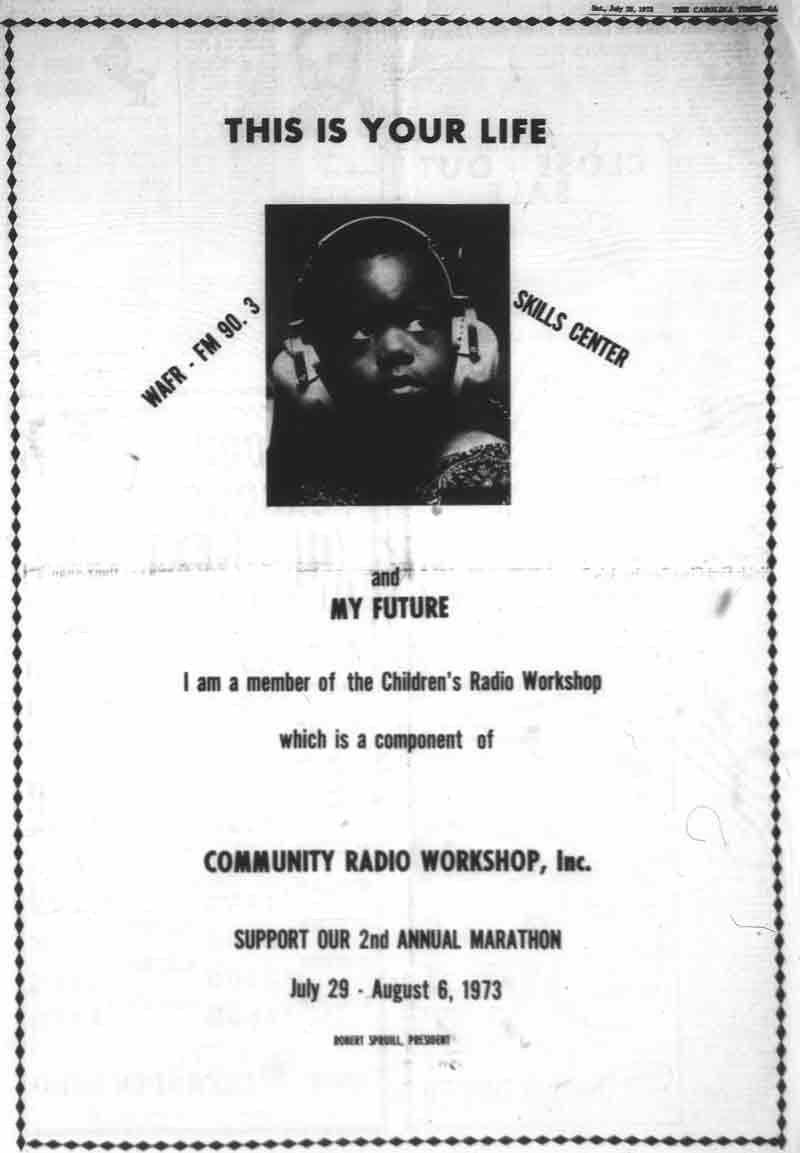

Sponsored by Community Radio Workshop, Inc., the station hosted public workshops on black politics and history as well as free training in radio broadcasting and other vocational skills.

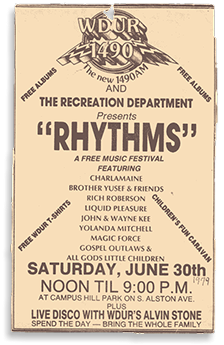

WDUR was perhaps best known for its concert series, "Rhythms."

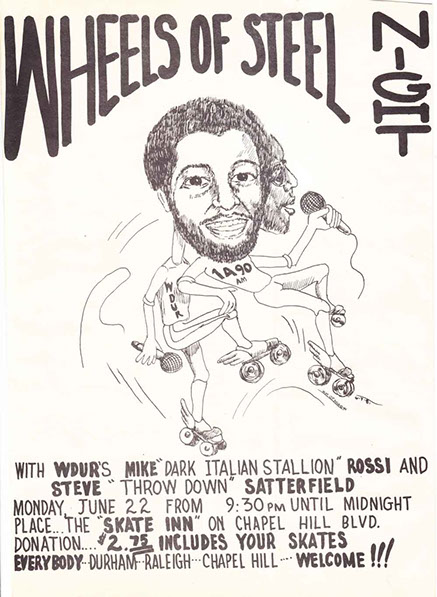

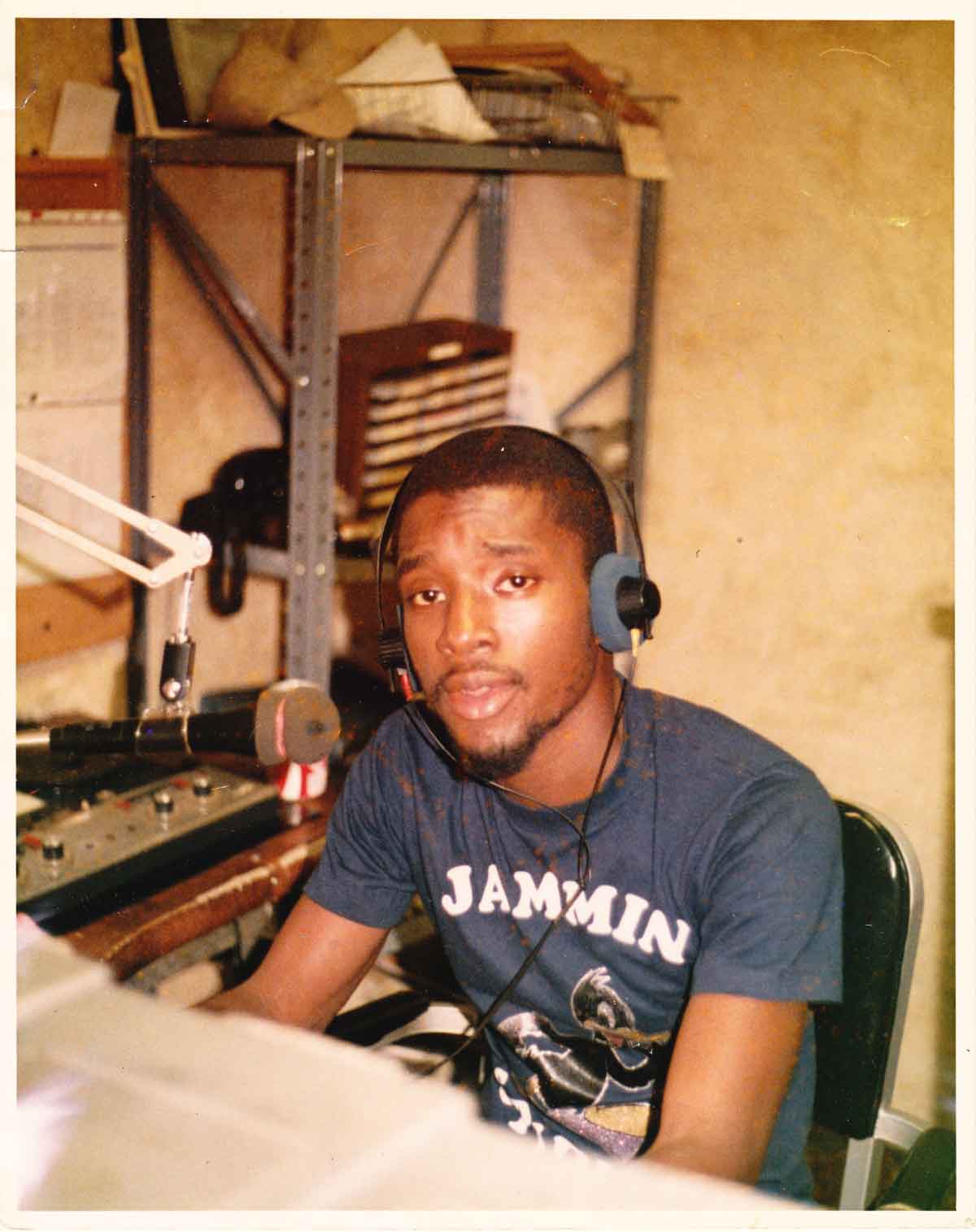

Satterfield started at WSSB and in later years also broadcast on WSRC and WNCU. He is seen in the photograph here and the drawings above and below from WDUR advertisements.

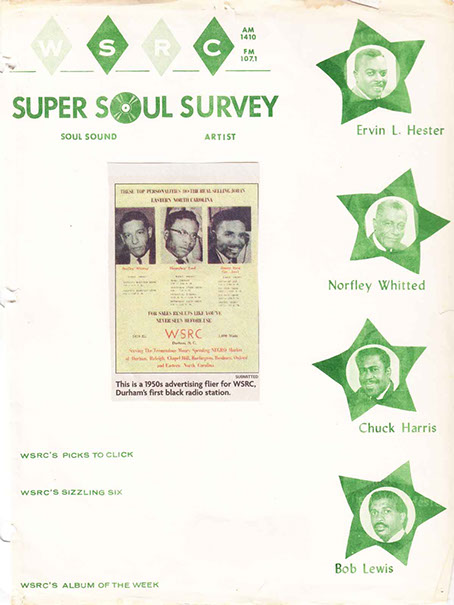

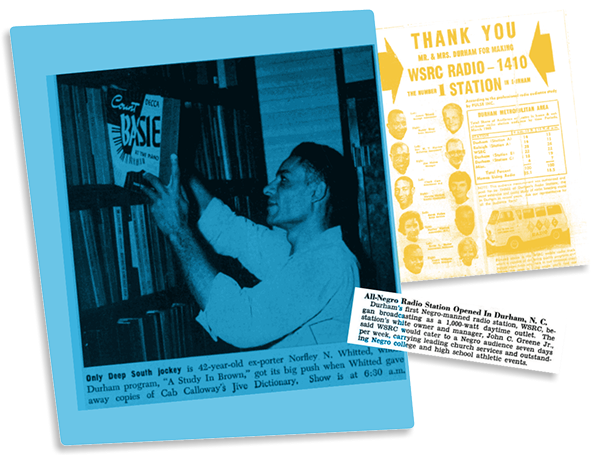

Very few African Americans managed to enter the radio industry before World War II. But in the early 1940s, Whitted hosted CBS broadcasts of performances by the Dixie Hummingbirds and other black artists traveling through Durham. A 1947 article in Billboard magazine even identified Whitted, who by then had a regular show on Durham's WDNC station, as one of only sixteen black radio announcers in the United States at the time.

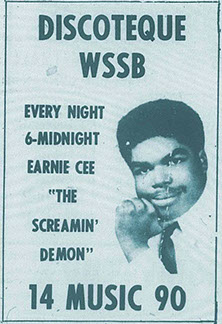

WSRC began broadcasting in Durham 1954 as the first so-called “Negro-oriented” station in North Carolina. Announcers made the station popular by playing R&B and soul music and staying active in Durham's black community. Still, by the 1960s some black Durhamites objected to the fact that the station was owned by whites.

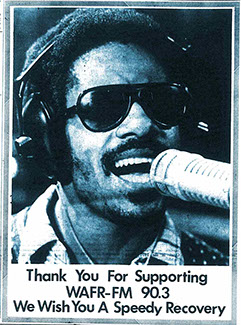

Many African American Durhamites wished for a black-owned broadcaster. In 1971, a group of local activists launched WAFR as Durham’s first black-controlled station.

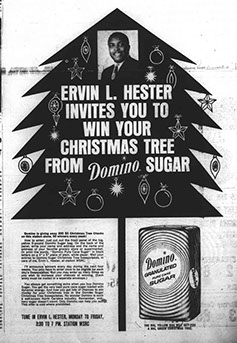

WSRC launched the media careers of several well-known African Americans announcers such as “Chuckie” Harris and Ervin Hester. Hester later became the first black anchorman on WTVD television, where he hosted his own talk show.

Stevie Wonder was scheduled to perform a benefit concert for WAFR in 1973, but was injured in a car accident on the way to the show and had to cancel. WAFR’s finances and public reputation unfortunately took a hit as a result.

---i-want-you-(a).jpg)

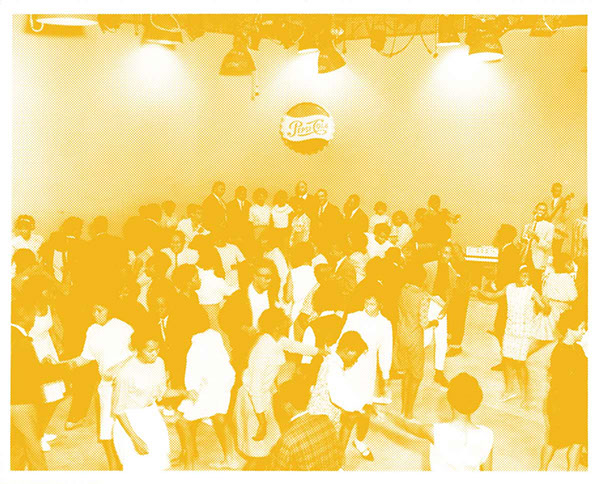

Barnes' early childhood memories of adults dancing inspired him to paint Sugar Shack. The painting was featured on the cover of Marvin Gaye’s 1976 album I Want You as well as in the opening credits of the popular television show Good Times. If you look closely, you’ll see the banner for Durham’s own WSRC radio station hanging from the rafters.

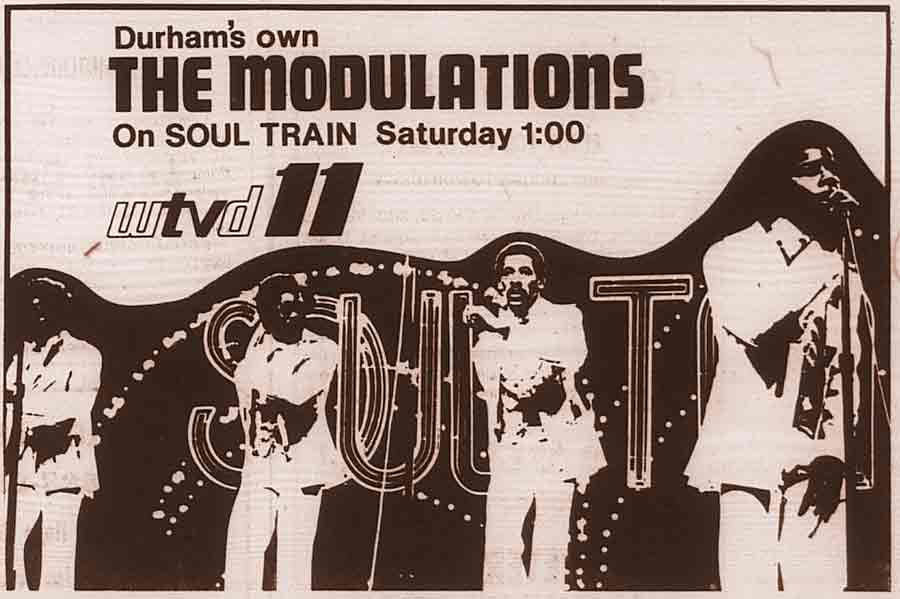

Lewis was one of the very few African Americans with a television show in the Jim Crow South. Teenage Frolics, which debuted in 1958, preceded Don Cornelius’ Soul Train by over a decade. Viewers tuned in to the show for over twenty-five years to watch local youth dance to the latest R&B hit records. Bands from the Triangle area also made live appearances. An invitation to dance on the set or perform live was considered a great privilege.